Your donation will support the student journalists of Lawrence Free State High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

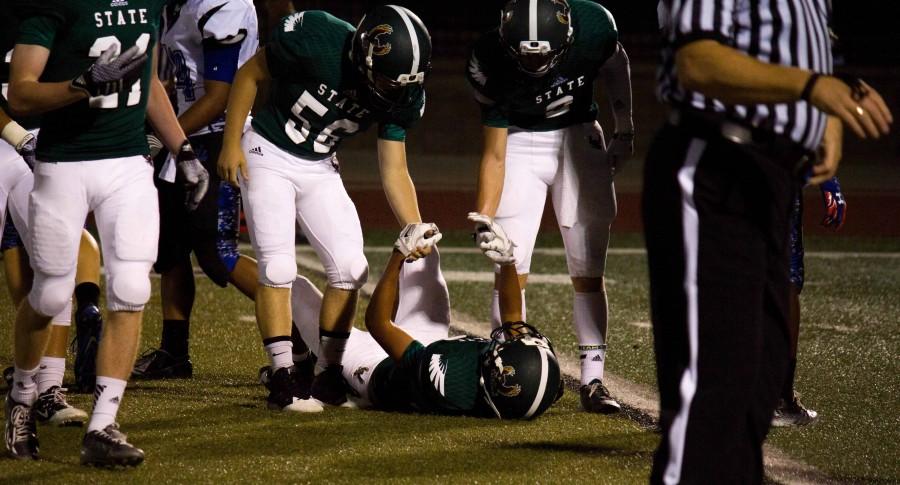

Seniors Jacob Allen and Joel Spain help a teammate to his feet during the varsity Homecoming game against Leavenworth.

Free State athletes recount concussions, close calls

October 27, 2014

Hoping to secure a spot on the varsity team, senior Briceson Junge plays hard on the last day of soccer tryouts. As Junge goes for a hitter, the goalie’s fist collides with his face. Junge immediately feels dazed, and athletic trainer, Ashley Frankian, comes to test him for delayed reaction and memory loss, common signs of a concussion.

With recent studies indicating nearly 30 percent of NFL retirees will get dementia or Alzheimer’s, concern mounts regarding the impact of head injuries sustained in high school sports.

In many sports—especially high-impact sports like football—injuries, specifically concussions, are common on the field. Senior Shane Hofer sustained a head injury last year while the Firebird football team battled Shawnee Mission East (SME).

“I don’t remember most of the game, or any of it,” Hofer said. “I’ve watched the film multiple times, but I couldn’t find a certain play. I think I got one (a concussion) in the first half and I just kept on playing, and it got really bad.”

Those at the game witnessed Hofer’s confusion and distress and were later able to tell him what happened.

During the remainder of the game, Hofer’s emotions surged as he tried to understand his surroundings in his altered, muddled state.

“I got to the sidelines and started yelling at our trainer because I wanted to go back in,” Hofer said. “… I guess I threw a couple water bottles at people. It was kind of weird, because it’s almost like you’re possessed or something like that.”

Senior Jackson Reed also got a concussion while playing football. During the first week of the season, a teammate hit Reed at practice.

“I remember going to practice (and) getting hit,” Reed said. “Then, I remember talking to the trainer and going home.”

After a concussion occurs, Frankian begins investigating the injury.

“(I run) what’s called a SCAT 3 test (on the players),” Frankian said. “It’s a concussion protocol that we follow that tests their (athletes’) cognitive function, their balance and their symptoms.”

If Frankian suspects any cognitive damage, the player is sent to a physician. The physician then decides whether or not to clear the player, sending him or her back to Frankian for a week of recovery exercises.

“It takes four days, … as long as symptoms don’t return,” Frankian said.

However, Frankian notes flaws within the protocol for concussion injuries.

“It’s hard to tell because a concussion is a subjective injury, so they have to tell me how they feel,” Frankian said. “You can’t always see it.”

Student athletes are well aware they cannot play while concussed, and as a result, Frankian says she sees more students withholding information about possible head injuries for a variety of reasons.

That being said, Hofer did not feel pressure from coaches to play after his injury, and head football coach Bob Lisher agreed safety is a top concern for the football coaching staff and for football teams across the country.

“There are rules in place now where they are trying to eliminate a lot of head-to-head contact,” Lisher said. “There’s more emphasis on keeping the head out of the game (and) just making sure that the head is for protection, not for a weapon.”

However, due to a love of the game and a feeling of responsibility to their teammates and coaches, many players admit returning to practice before they fully healed.

“You always want to be tough,” junior Sam Skwarlo said. “I’d say it was definitely self (pressure). I just told myself I was going to play.”

A group of defenders stepped on Skwarlo’s foot during the first football game of the season. What Skwarlo first thought was a bruise turned out to be a lisfranc tear, requiring many screws and plates to fuse his bones back together. He was out for the season and utterly devastated.

“I’m not that much of an emotional guy, but I was bawling my eyes out,” Skwarlo said. “I can’t think of any days that are much worse than that one. It was a pretty big blow.”

At a volleyball tournament in Lee Summit, junior Allie Knapp felt similar frustration over her inability to play after being concussed during the game.

“I just didn’t want to let my team down,” Knapp said. “They had so many games … I wanted to come back so bad and play. It was one of those things where I couldn’t speed up the recovery, you know. It’s my brain.”

Knapp suffered from common concussion symptoms: memory loss, blackouts and disorientation.

“After making contact with the ball, I hit the side of my head on the ground, and immediately it just totally got swollen,” Knapp said. “I couldn’t see out of this eye, but I could see in my peripherals the big bump. After I hit my head, I tried to get up right away, and I fell back down. I opened up my eyes, and it was just black. I blinked, like, five times, and it was still black.”

Knapp continued to play after her injury, but quickly realized that she needed to sit out—a decision her coach supported.

Across the athletics program, injured athletes are supported and encouraged to heal instead of forced back into competition before they are ready.

Frankian agreed coaches have a significant role. After a serious injury, she lets the coaches handle the players’ emotions so she can focus on splinting and ensuring they make it to the emergency room if necessary.

“Sometimes coaches will actually hold them out longer than I will,” Frankian said.

Junior Kierstin Hutfles experienced this support as she dealt with multiple knee injuries and underwent three surgeries due to those injuries in her high school career.

Hutfles did not feel pressure from head soccer coach Kelly Barah to return to the field before she was ready.

“Barah was amazing,” Hutfles said. “He was more sad for me, so in that sense it kind of made me want to prove to him that it was no big deal, just a little hiccup.”

Over the course of two and a half years, Hutfles has undergone multiple surgeries. Not only did her injuries require knee reconstruction, but now she is healing from another surgery after the reconstructed knee broke in half while jumping for a header in a soccer game.

Hutfles’ body rejected the pin used to reconstruct her knee, which weakened the joint and caused increased susceptibility to further injuries.

“It’s hard getting around, and it wears you out being on crutches, so I’m always exhausted,” Hutfles said. “With this straight leg, getting shorts up is hard.”

Recovering from trauma while playing in high school can cause a large upset in one’s schoolwork. Injuries, especially to the head, can hinder one’s academic performance.

“It is hard,” Hutfles said. “I’ve missed about a week of school now, and I’m just getting caught up, making up tests and homework, especially with all the AP classes I’m doing.”

Knapp also missed a week of school after her concussion.

“I was so behind with school work, and when I finally came back, I had so much more,” Knapp said.

Knapp faced many restrictions during her time at home to keep from over-stimulating her brain.

“I could do 10 minutes and then I’d have to stop, just because I didn’t want my brain working, or thinking.” Knapp said. “Even if it didn’t hurt me or bother me, they just wanted my brain resting.”

Permanent neurological damage could result from overworking the brain too early after an injury. To help with this process, Frankian assigned Junge a workout regimen that eased him back into soccer gently.

“There were some days where I had to skip one day (of physical therapy) because my head started to hurt,” Junge said. “It’s like you can’t concentrate really at all, and I was really sensitive to light.”

With football, both Hofer and Reed had to wait until headache symptoms went away before they also started a routine of exercise that gradually worked them back into the sport.

Even after the recovery process is complete, players fear reinjury because multiple concussions are a cause of termination for many athletes.

“Sometimes I think about it, going in, before a game, but during a game you’re getting hit in the head so many times that (getting a concussion) is the last thing on your mind,” Hofer said. “Throughout the week I’ll think about it sometimes, because, you know, if I get one more, I might never play again.”

Junge uses common sense off the field to decrease risk of reinjury.

“I wouldn’t go and try to do something else that would get me hurt again, … but when I was actually playing, I didn’t feel restricted by it,” Junge said.

While some athletes take precautions, others hang up their jerseys to preserve their health. Skwarlo’s older brother and Free State alumnus, Stan Skwarlo, is one such athlete.

Although Stan Skwarlo played football in the past, he gave it up to pursue his interest in the medical field. He ruled out football after considering the potential for serious brain damage.

Sam Skwarlo, on the other hand, believes the benefit outweighs potential long-term cognitive damage.

“I’m willing to take the chance,” Sam Skwarlo said. “… Especially since I’ve always wanted to play college football.”

Even though all sports have risks, Hutfles also believes the game is enough to sway those fears.

“Your brain is more valuable, but I think you should definitely have the option of playing the sport you love,” Hutfles said. “Even if it can cause injury.”

Instead of keeping students from sports, Knapp suggested alternative precautions be taken. She stressed the importance of a mandatory impact test.

Frankian elaborated on how the test works, describing the series of computerized tests that evaluate your memory, reaction time, speed and other cognitive functions.

“All athletes can take it before their season starts, and then if you were to get a concussion you can to certain doctors and retake the test,” Frankian said.

If the results from the second test prove to be worse than those of the first, the player will not be cleared to return.

Because Knapp hadn’t taken the impact test before, her doctors struggled to make a diagnosis based on her score.

“They didn’t know what I would be normally, so it was hard for them to distinguish how bad it was,” Knapp said. “I feel like in the future, that should just be mandatory, no matter what sport it is.”